Gotta finish taking out the trash and i'm mad…. aint mad, I know what this country about, but the other day we elected this one dude again for president and yeah. Not really in the mood for this newsletter shit but been wanting to be consistent.

I don't think we have given yall enough vibes on black modernist architects. At the start of Hood Century on IG, I aint know there was black architects or - I wasn't deeply knowing about no architects at all, def didn't know that there was brothers. That every state has that “1st black modernist arch” shit happening right now (and since 2020) and I'm like - niggaahh its mass cats!

Just learned bout Mr. Alonzo Robinson from Wisconsin, another brother from Pittsburgh and one in Cincinnati just the other day too. I do know NOMAS has a list of their members (and AIA has its black architects listed from that era.) You think we would know haha. But for some reason or another I like the way I am finding out about these brothers and sisters.

Anyway - I want to introduce yall or re introduce yall to a couple im fucking w. Peep!

Black Modernist Architects

(Black Modernism: Modernism with the consideration of Black folks, our infrastructure, the things we made and the places we adapted to be ours. Defined by Hood Century, 2020.)

Amaza Lee Meredith

Amaza Lee Meredith, 1958, Petersburg, VA.

Amaza Lee reminds me you don’t need to be no architect to build!!

A queer, Black woman born in 1895, 30 years after slavery ended, in the industrial town of Lynchburg, Virginia. She had the craziest view of probably the most transformative time in American history; Jim Crow, The Great Depression, The Great Migration.

She moved to NYC with her sister and was an active local during the Harlem Renaissance. The sisters shared an apartment out there in Harlem while Amaza went to college to study Fine Art and Art Education at the Columbia Teachers College.

When she returned to VA, she founded the Art Department at Virginia State University, introducing her students to Art as world-building.

Amaza had no formal education in architecture. Her pops was in the carpentry trade though, and she learned about building and joinery from him, even how to draw architectural blueprints.

In 1939, she completed her architectural debut, a home on the edge of VSU designed for her and her partner - named Azurest South. “Az u rest”.

I’ve noticed during these last 5 years or so of intentionally studying Black folk and our design choices that Art Deco, International Style, and Streamline Moderne kept popping up! The influence of the spaces we were existing in during the 20s and 30s; the jazz clubs, churches and train stations.

Amaza’s design intention shows it too. The popular Modernist thought of the time but also the design of the infrastructure that she was living in.

Azurest South, built 1939.

International Style: the geometry, volumes and lines

Art Deco: the color and the patterns across the floors, ceilings, and walls

Streamline Moderne: clean lines, “pure form”, the single rectangular form of the house with rounded edges

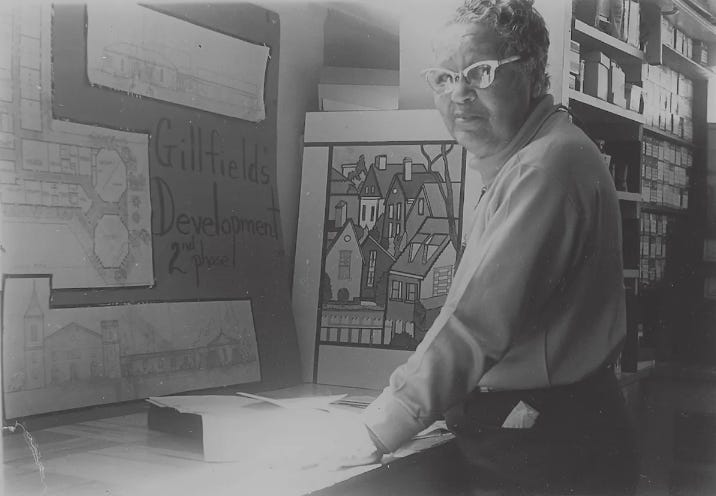

Alonzo Robinson Jr.

Z just put us on and wow. The first registered Black Architect in Milwaukee. The Wisconsin Historical Society already has 51 spots listed by him, and they’re discovering or crediting him with more rn.

Born in Asheville, North Carolina in 1923, Robinson grew up in Delaware and went on to study Industrial Arts at Delaware State University (then called “Delaware State College for Colored Students”).

Part way through his education he was drafted into the Navy as a Technical Sergeant, to be stationed in Japan during WW2. When he returned to the states after the war, he went on to study architecture at Howard University, receiving his degree in 1951. In 1954 he accepted a job as an architect in Milwaukee with the City Bureau of Bridges and Buildings.

Entering the field of architecture at the start of the Civil Rights Movement, Robinson went on to serve the city for more than 40 years, designing public buildings like churches, the central city plaza and projects for members of Milwaukee’s Black community.

Central City Plaza, Milwaukee, 1973

"Developed by the Central City Development Corporation (CCDC) which was a Black development group organized by some of Milwaukee's most prominent Civil Rights leaders... The project was to become the state's first Black developed, owned and operated commercial complex, with intentions of reclaiming the city's African American commercial hearth last achieved during the Bronzeville era."

Mount Carmel Missionary Baptist Church, Milwaukee, 1974

The Milwaukee Star, one of the city’s Black newspapers, described Alonzo Robinson’s designs in 1974 as “highly sensitive”. I think of that in terms of environment when I look at them zig zag lines of a couple of the churches he designed - something I notice often in the roof’s of our modernist design. Something we researchin’ and naming “ROOF ROOF”. Haha. Peep #roofroof on ig.

Church of the Living God, Milwaukee, 1968

Roger Margerum

Roger is one of the illest black modernist designers to ever do it.

The interior and exterior of Ingram House (1959), south side Chicago, IL, by Lee Bey.

After he closed his full-time practice in 2000, Roger’s wife, Fran, asked him to design a house for her. Although he’d lived in apartments his entire life, he gladly granted her wish — with one condition.

“I had to satisfy her, but also myself,” Margerum says. “And the only way to satisfy myself was to design something architecturally significant. I believe I’ve done that. To my knowledge, no one before has used the 45-degree polygon as a rigid module.”

Margerum House aka “45 Degree Polygon House”, Detroit, MI

John Moutoussamy

John Moutoussamy studied at the IIT School of Architecture in Chicago on the GI Bill after serving in World War II. During his time at IIT, he studied and worked alongside prominent names of 20th century modern architecture such as Mies van der Rohe and K. Roderick O’Neil.

Over 4 decades, Moutoussamy designed buildings from residential towers to schools and health care facilities, but his most prominent work remains the The Johnson Publishing Company Building, dedicated on May 16,1972. The first structure in downtown Chicago built by an African American.

11 storeys high, The Johnson Publishing Company Building was home to a growing media empire, including the Ebony and Jet magazine offices, describe by Moutoussamy himself as a building “designed as a place where Black creativity could blossom.”

“The Black art, the horizontals, the glass, the marbles, the fabrics, the warm colors; all these elements integrated into one grand design express the essential meaning of our firm. It expresses openness, openness to truth, openness to light, openness to all of the events swirling in all of the Black communities in our country.”

I mean, this might be one of the most iconic archival footage of Chicago black history.

Excerpt from Black Journal ep. No 324 via HOOD CENTURY TV.

This is part 1 of our black modernist architect index. If yall have more photos or videos of any of these spots, share them here!

P.S Taking a break from ig. See you soon.

Written and edited by Coop and Savannah.

#blackmodernism

mo on amaza via jessica lynne ❤️🔥 https://www.southerncultures.org/article/that-which-we-are-still-learning-to-name/